Turkey and Syria's Assad: Is reconciliation on the horizon?

As some Arab states renormalise relations with Syria's regime, Turkey remains the only power actively sponsoring opposition forces in the country.

Yet Ankara faces growing domestic and international challenges vis-à-vis Syria, raising the spectre of future Turkish-Syrian reconciliation.

Ultimately, Turkey is not categorically opposed to reopening formal relations with Bashar al-Assad’s regime. That process, however, must address Turkey’s security and economic concerns in relation to northern Syria as well as the agendas of the US and Russia.

"As more Arab states renormalise relations with Damascus pressure will increase on Ankara to follow suit"

Turkish domestic politics play a role

At home, the issue of Syrian refugees places substantial pressure on Turkey’s government against the backdrop of an economic crisis.

Beginning in 2011, the Justice and Development Party (AKP)’s principled stance in favour of ousting Assad and hosting Syrian refugees was initially popular among Turks.

During the early phases of Syria’s civil war, Ankara’s narratives about Islamic values informed widespread attitudes in Turkey about the need to welcome Syrians.

But over the years xenophobia and anti-Arab bigotry, alongside exhaustion from caring for 3.7 million displaced Syrians in Turkey, have led to waning support for this narrative.

Deteriorating economic conditions in Turkey, underscored by an 83 percent depreciation of the Turkish Lira since last year, have hit the average Turk very hard.

Syrian refugees have become a scapegoat for many in Turkey with the ‘banana jokes’ saga of 2021 highlighting this unfortunate reality.

Some Turkish opposition parties have opportunistically co-opted these resentments throughout the country to strengthen their support base.

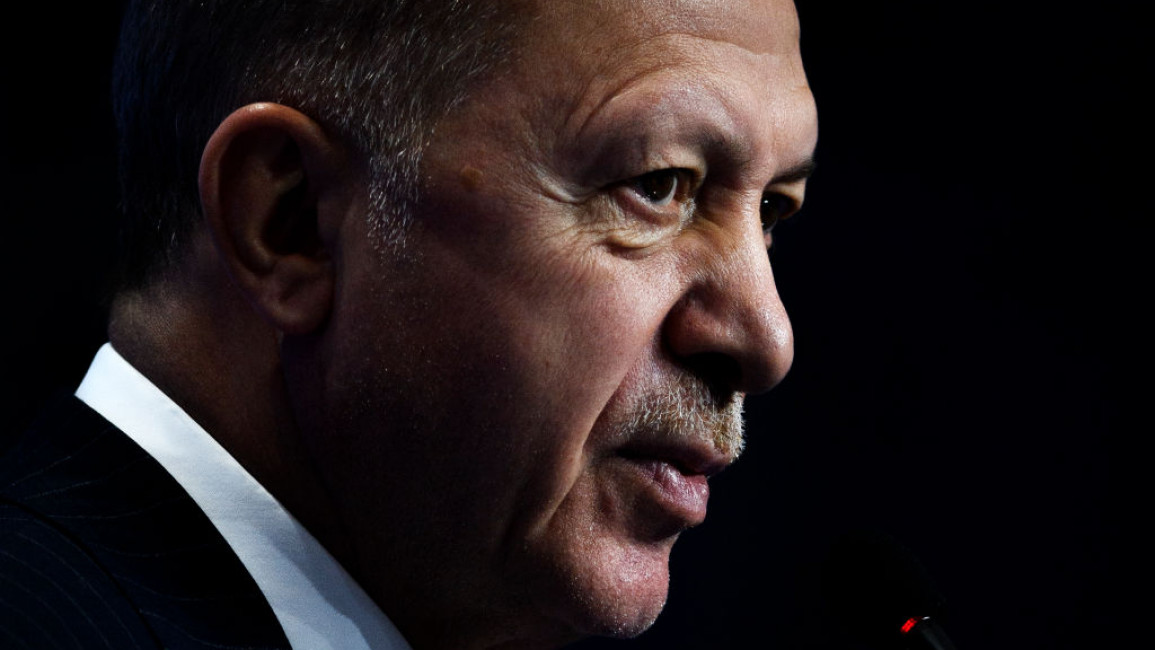

The Republican People’s Party (CHP), Turkey’s largest opposition party, rails against President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Syria policies with the understanding that anti-refugee sentiments might help them win next year’s elections in Turkey.

A CHP victory in 2023 as the head of a new anti-Erdogan coalition would likely result in Ankara adopting a drastically different approach to Syria.

“The CHP criticised Erdogan’s Syria policy,” said Joshua Landis, who heads the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma, in an interview with The New Arab.

“They claim it has been a disaster, costing Syria billions with nothing to show for it. They say that they would withdraw Turkish troops and open a dialogue with Assad.”

A CHP-led government would probably increase efforts to return Syrian refugees to so-called “safe zones”, which are the buffer zones that Turkey established in northern Syria during Operation Peace Spring in 2019.

In theory, these are areas where Syrians can return without fear of regime reprisals.

Realistically, however, Ankara cannot guarantee returnees’ safety and security upon deportation to Syria.

This is not only because of the regime in Damascus but also due to extremists in the opposition, and ongoing fighting.

|

|

Regional considerations at play

Regional pressures also influence Turkey’s considerations. As more Arab states renormalise relations with Damascus pressure will increase on Ankara to follow suit. However, there are many sensitive geopolitical and security considerations in play.

Turkey has committed itself to a more pragmatic foreign policy, working to mend fences with key regional players such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Israel.

The Emiratis have announced billions of US dollars in investments in Turkey that are crucial to any economic recovery. Similar rumours of a warming in Saudi-Turkish relations – and subsequent economic and defence deals – appear imminent.

Still, such dealings almost always have strings attached. Ankara has already worked to temper Muslim Brotherhood broadcasting in Istanbul, suggesting similar pressure could come from Abu Dhabi on the Syria file.

Indeed, as Turkey improves relations with Arab states, the pressure to be more amenable to Abu Dhabi’s interests, including wider acceptance of Assad’s ‘legitimacy’, will increase.

"Ankara-Damascus relations will remain frosty regardless of any potential renormalisation"

The future of Syria-Turkey relations

Although much remains to be seen with respect to Turkish elections and regional shifts towards pragmatic relationships following a tumultuous decade, Ankara-Damascus relations will remain frosty regardless of any potential renormalisation.

The countries have effectively been at war for 11 years, suggesting substantial diplomatic engagement is needed for the two states to restore friendly ties within the context of the Adana Agreement, which prevented a war between them in the late 1990s.

This is particularly true if Erdogan remains in power, as the Turkish leader has traded rhetorical bombshells with Assad since 2011. Nonetheless, Assad will welcome any degree of peace with Ankara regardless of AKP or CHP leadership.

“Turkey holds the key to Syria’s long-term political stability, not only politically but in economic and humanitarian terms as well,” Serhat S. Çubukçuoğlu, a senior researcher in geopolitics and a doctoral candidate in International Affairs at Johns Hopkins SAIS in Washington, told TNA.

However, the status of Idlib, which remains under the control of Turkish-backed rebels, and the position of the US-backed People’s Protection Units (YPG) will remain two contentious issues between Ankara and Damascus.

For the Syrian regime, controlling every inch of Syrian land is important to completing its ‘victory’.

However, Assad’s military violently retaking Idlib would also exacerbate the Syrian refugee crisis in Turkey as many of the four million Syrians currently in Idlib would flee across the Turkish border.

Mindful of public attitudes in Turkey toward Syrian refugees, Ankara wishes to avoid such a scenario.

“Turkey under Erdogan will be unlikely to relinquish north Aleppo or Idlib,” explained Landis.

“Various Turkish opposition groups have said that they would withdraw from Syria. Many of the inhabitants of northwestern Syria would like to remain under Turkish control and acquire Turkish citizenship. Much of the infrastructure in these regions is dependent on Turkey. The Turks may hope to annex northwestern Syria in the future, but many Turks will not want an additional three to four million Arabs.”

Other experts doubt that Ankara would annex Idlib or other parts of northern Syria, noting that Turkish interests here are largely tied to security concerns in the current context.

“Turkey has no interest in annexing Idlib or any other Syrian territory,” explained Çubukçuoğlu.

“The Turkish military presence is temporary to prevent an autonomous YPG/PKK belt along northern Syria that would form an existential threat to Turkey’s territorial integrity.”

As he noted, “Turkey’s vital interest is to not let the YPG form a continuous belt along northern Syria and gain warm water port access to the Mediterranean.”

Nonetheless, Idlib’s future remains unclear given today’s circumstances. Any Turkish miliary presence will be central to future Ankara-Damascus talks.

Turkish development efforts in parts of northern Aleppo suggest that Ankara could be interested in a land swap given its lack of preferable options.

Still, Assad’s limited appetite for absorbing millions of people whom he views as a direct threat to his rule and Moscow and Damascus’s disinterest in land deals with Turkey further complicate the picture.

These two issues — Idlib and the YPG — are unlikely to be settled within the context of Ankara and Damascus’ bilateral relations because they concern the interests of the US and Russia.

"As Turkey improves relations with Arab states, the pressure to be more amenable to Abu Dhabi's interests, including wider acceptance of Assad's 'legitimacy', will increase"

Moscow strongly desires this reconciliation between Ankara and Damascus while Washington would firmly oppose it so long as Assad remains in power and refuses to make concessions demanded by US and other western officials.

“I do not think that the US is particularly keen to see Turkey reconcile with Assad under current circumstances because that would mean Assad, and hence Russia, extending their control to the north and northeast and uprooting US-supported groups or even risking an armed conflict with US special forces there,” Çubukçuoğlu told TNA.

“Overall, it would ultimately be in Turkey’s interest to reach a negotiated settlement with Assad. But it depends on how other actors in the region would view this rapprochement and how they’d react to it.”

For Ankara, peace with Damascus will require the YPG to be disarmed, dissolved, integrated into the Syrian state, or militarily destroyed. Unless and until the YPG meets one of these fates, Ankara will probably continue low-level military campaigns in northern Syria that infuriate Damascus and nearly all Arab capitals, save Doha.

“Turkey can practically annihilate the YPG from all the remaining strongholds near the Turkish border and even extend its area of control to other enclaves such as Manbij,” reminded Çubukçuoğlu.

Ultimately, Washington’s relationship with the YPG is pivotal to the future of Turkey’s position vis-à-vis northern Syria.

If the US continues courting the YPG, which is highly likely as the group provides Washington with a foothold in oil- and gas-rich parts of Syria and is central to fighting the Islamic State and countering Iran, Syria alone probably can’t meaningfully assuage Ankara’s security concerns.

With Assad’s regime essentially functioning as Russia’s proxy, the YPG’s dissolution or integration into the Syrian state would probably require a grand bargain involving Moscow and Washington.

Mindful of US-Russia hostilities vis-à-vis Ukraine and the West’s financial warfare against Moscow, only the most optimistic analysts can expect such a grand bargain over Syria in the near term, although it is crucial to any significant shift in relations between Turkey and Syria’s Assad.

Giorgio Cafiero is the CEO of Gulf State Analytics. Follow him on Twitter: @GiorgioCafiero

Alexander Langlois is a foreign policy analyst focused on the Middle East and North Africa. Follow him on Twitter: @langloisajl