Honey fraud in Yemen leaves bitter taste

Fatima has just been told that the 7kg of honey she has been sold is impure.

"Allah is sufficient for me and he is my guardian," the 50-year-old says in response.

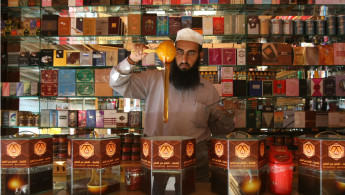

She was informed by Mabrouk Salmeen, one of Souk al-Qatan's oldest honey traders, who told al-Araby al-Jadeed the real value of Fatima's honey was a quarter of the $150 she paid.

|

How could I explain the taste of premium honey to someone who does not know what the Sidr tree is? - Mansour Mehsen Batis, established Yemen honey trader |

The news is devastating for Fatima, and for Salmeen and other tradesmen - it is another blow to the reputation of the souk in Hadhramaut, the largest honey market in the Arab world, in a country famed for its sweet product.

Honey boo boo

"A lot of people come to me complaining about counterfeit honey," says Salmeen, a beekeeper for 60 years. "The honey trade in Yemen has become tarnished by fraud, and the profession is now being taken over by the weak-minded."

For centuries, Yemen has been famed for producing the best honey in the world. The best of the best comes from bees who gather nectar from the Sidr, a sacred tree mentioned four times in the Quran and noted for its medicinal qualities. Its nectar is so potent that bees die after only a few trips.

| Life on the streets of Yemen's battle-scarred capital - read Abubakr al-Shamahi's account |

But Abdullah Bamoumin, another beekeeper at the market, says it is an influx of inferior foreign products that has damaged the trade. "People started coming up with creative methods to sell counterfeit honey in 2008," he says, pointing the finger at Pakistani and Turkish traders. "The trust between the buyer and seller has suffered."

Unscrupulous traders "cut" high-quality Yemeni Sidr honey, which often trades at $100 a kilo, with foreign products worth far less - and pass it off as pure Sidr honey.

Beekeeper Salem Bazheer, 50, says the fraudsters have other methods. "There are beekeepers who feed their bees sugar syrup to increase production. With this method it would be hard to verify if the honey is Sidr honey."

A third method is simply passing off Peshawari honey as Yemeni. One beekeeper at the souk told al-Araby that some of this product doesn't even come from bees - it is ersatz, and made in a laboratory.

Show me the honey

Novice buyers are often caught out - but even experts fall into the trap. "I have worked in the honey industry for 20 years, and I have been deceived many times," said Dafer, another trader at the market.

But traders are fighting back. Mansour Mehsen Batis, whose family has traded honey for generations, says he has three methods to spot inferior product.

"How could I explain the taste of premium honey to someone who does not know what the Sidr tree is?" he asks. Sugar-syrup honey is far sweeter than Sidr honey, he adds.

Secondly, Sidr honey is sticky and cannot be washed from the hands easily, unlike inferior products.

The colour can also be a giveaway - the finest Sidr honey, which can sell for $750 a gallon, has a brown-reddish hue that does not change over time, unlike products created to mimic it.

Odour can also distinguish pure honey from fake, according to Mehsen, as the Sidr tree has a unique, aromatic smell. "Anyone buying honey should be familiar with the Sidr tree smell," he says.

Honey is a buzzing business in Yemen. The country's central bureau of statistics says that production in the past 10 years has hit 5,000 tonnes a year, with a value of $800m.

Exports were worth $13.6m in the fourth quarter of 2014, according to the ministry of agriculture - about a fifth of the money generated by Yemen's oil industry. Saudi Arabia is the biggest export market.

A sting in the tail

The president of the Yemeni Association for Consumer Protection, Fadl Mansour, said beekeepers themselves were to blame for the industry's problems, saying there were no minimum standards for Yemeni honey.

He added that fraud could only be curbed by banning the import of large amounts of honey. "Only small jars of no more than 1kg each should be allowed," he says.

Testing honey quality is also complicated, he said, and it was often a case of "buyer beware".

Mansour urged the Yemeni government to establish associations for beekeepers and producers, and said the industry needed to introduce certification marks to all honey products as evidence of compliance with standards.

Such measures, he said, would help sweeten beekeepers' lives and keep honey an important source of income in such an impoverished country.

This article is an edited translation from our Arabic edition.