Belt and Road Initiative: As America's power fades, China lures Arabs into its sphere

The East Asian world power has met a much more positive reception in the Arab world, however. Across North Africa and Western Asia, Arab leaders are receiving their Chinese counterparts with open arms.

"Chinese investment, whether under the BRI rubric or not, comes with no criticism of local political systems, policies, and practices and no demands for alignment with China on international issues," said Chas Freeman Jr., a former American ambassador to Saudi Arabia and a senior fellow at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

"China is silent on political and religious issues and presents itself as having no agenda other than access to Arab energy resources and markets and the enhancement of connectivity with Arab societies to their benefit as well as that of China."

Despite the divisive politics of the Middle East, China has avoided embroiling itself in any of the region's civil wars and other international crises.

Even rivals such as Qatar and the United Arab Emirates have welcomed Chinese capital without China becoming involved in the ongoing dispute between the two regional powers. In Iraq, Libya, Sudan, and other countries struggling with political violence, meanwhile, Chinese investments have continued apace. Even Yemen is trying to court Chinese investors.

Reapplying a diplomatic tactic that has worked well in Myanmar, South Sudan, and other fragile states, China has poured money into Arab economies while refraining from questioning the domestic and foreign policies of its Middle Eastern allies – even if their actions threaten Chinese investments. Adopting this approach has allowed China to forge economic relationships without picking political sides.

"The UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt are at the top of the list of Arab states that are taking advantage of Chinese interest in the region, with Kuwait and Oman also working with Chinese firms," observed Dr Jonathan Fulton, an assistant professor of political science at Zayed University and author of China's Relations with the Gulf Monarchies.

"With Arab states looking more widely for foreign direct investment and Gulf states undertaking massive infrastructure construction programs as part of their 'vision' development plans, there is a lot of synergy with the BRI."

|

|

| Read also: Renewable energy: How the Gulf is preparing for a future without petroleum |

Much of China's attention has focused on the Persian Gulf, whose hefty oil reserves can feed the world power's ever-growing energy consumption. Chinese investors have backed several of the region's largest projects, including Madinat al-Hareer in Kuwait, the Special Economic Zone Authority of Duqm in Oman, and Khalifa Port in the UAE, all components of the BRI's wider plans for the Gulf.

"Over twenty countries in the region have formally signed onto the BRI, and China's courting of countries that have great animosity between them has not caused any diplomatic upsets so far," said Dr Willem Theo Oosterveld, a senior fellow at the Hague Center for Strategic Studies.

"However, it's still the early days of the BRI in the Middle East, and this region will – for multiple reasons – be the hardest nut to crack. It remains to be seen if China's non-interventionist approach can hold in the long run."

While the Chinese reluctance to intervene in Arab countries' internal affairs is yielding economic and political benefits for the time being, the BRI's emphasis on international trade has come at the cost of limiting China's diplomatic and military sphere of influence in the Middle East.

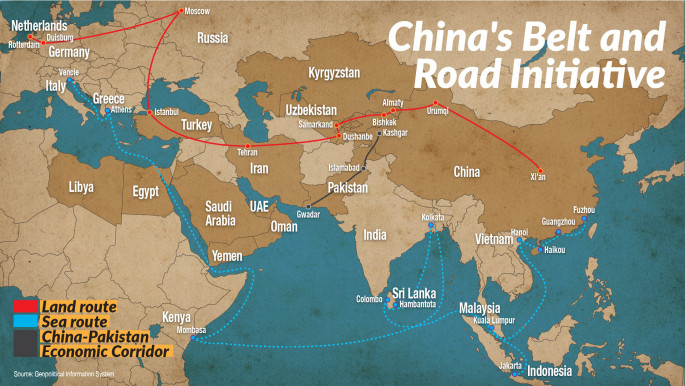

Article continues below graphic

Britain, France, Russia, and in particular the United States have spent decades cooperating with Arab countries from Egypt to Yemen on counterinsurgency, counterterrorism, and other geopolitical investments that have contributed to long-lasting ties. Even so, American interventions in the Middle East have had their own price.

"In many ways, Arab countries find China an attractive partner for the same reason they once did the US," Freeman, author of Interesting Times: China, America, and the Shifting Balance of Prestige, said of the new Chinese role in the Middle East.

"Until the end of the Cold War, the US had no agenda in the Gulf other than assured access to energy supplies. That is no longer the case. The US has intervened militarily in the region for its own purposes, not to advance the interests of local partners."

|

In return, China only requests that Arab countries ignore its crackdown on Uighurs and respect its diplomatic suzerainty over Taiwan |  |

The BRI frames economic partnerships between China and its Arab allies as relationships built on mutual self-interest, enabling China to escape the military and political quagmires in which the likes of Britain, France, Russia, and the US have often entangled themselves. In return, China only requests that Arab countries ignore its crackdown on Uighurs and respect its diplomatic suzerainty over Taiwan.

"China has a clearly articulated vision for the Middle East in the BRI, with the Arab Policy Paper from 2016 providing a broad set of regional priorities for Beijing, and initiatives like the China–Arab States Cooperation Forum, the China–GCC Strategic Dialogue, and the Belt and Road Forum in April being used to drive cooperation," Fulton told The New Arab.

"For several Arab states, this is an opportune moment for China to engage more deeply, as there is a sense that the regional order has been undergoing transformation and there's more space for extra-regional states to participate."

The BRI's economic focus and China's limited history in the Middle East have often helped Arab countries engage with the East Asian world power in a way that they would find difficult to do with their American or European allies, whose centuries of interventions in the Arab world have provoked countless controversies. While East Asian countries have historical tensions with China, no Arab ones do.

Western countries have the additional obstacle of accounting for political considerations that have rarely hindered China. After agents tied to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman killed the Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi, Western businesses, think tanks, and universities reevaluated their relationship with Saudi Arabia.

China, however, stood behind the Sunni monarchy, and bin Salman returned the favour by expressing support for the Chinese persecution of Uighurs, a Muslim minority group in China.

"China does not bring any historical baggage, making engaging with Beijing more palatable – not only for countries' leaderships but also for their peoples," noted Oosterveld.

"The BRI enables countries in the region to get a better bargain out of their extra-regional partners. Another factor is that engaging with China is unlikely to lead to antagonising existing relations with either the US or Russia."

Though China, Russia, and the US compete with one another in the Middle East and the rest of the world, Arab regional powers recognise that allying themselves with one side rarely precludes working with the other. Egypt has bought weapons from Russia and the US for decades. All the while, financial assistance from China and the US continues to flow into the North African country.

For its part, China understands that the US will remain the hegemon in the Arab world for many years to come.

"For Arab states, China isn't seen as a replacement for the US but rather as a diversifier," noted Fulton. "China simply can't provide what the US does, and, more importantly, it isn't interested in having the same kind of role as the US. That said, working with China is attractive in its own right."

Several Asian world powers are following China's lead. India, Japan, and South Korea – all rivals of China – are hoping to advance their economic relationships with the Middle East. While few countries have Chinese financial resources, many are willing to overlook the region's political risks for the sake of monetary gain.

China's treatment of its Uighur population has also caused alarm in the Muslim-majority countries of Malaysia, Pakistan, and Turkey, a sentiment that could spread to the Arab world in no time. Nonetheless, Chinese officials enjoy an obvious advantage in Middle Eastern capitals for now.

"In the end, the BRI is an offer of funding for projects that enhance connectivity, not a list of projects searching for funding," Freeman told The New Arab, noting China's popularity in the Gulf.

"It is an invitation, not a set of specific proposals for cooperation. As such, it is inherently appealing to Arab governments seeking foreign investment and augmented international connections."

Arab countries have little reason to reject the BRI, which presents them with substantial benefits at little short-term cost. As Middle Eastern and North African countries wrestle with how to overcome futures of economic stagnation and youth unemployment, China is giving them a financial lifeline.

"The BRI represents a vision of Eurasian connectivity in which the Middle East plays a positive role," Fulton told The New Arab.

"This is a big contrast with how the region tends to be perceived in Western capitals, where 'Middle East fatigue' has set in and it's generally seen in a negative light. China's offer of a competing vision of the Middle East as a hub in the New Silk Road is very attractive."

Austin Bodetti studies the intersection of Islam, culture, and politics in Africa and Asia. He has conducted fieldwork in Bosnia, Indonesia, Iraq, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Oman, South Sudan, Thailand, and Uganda. His research has appeared in The Daily Beast, USA Today, Vox, and Wired.