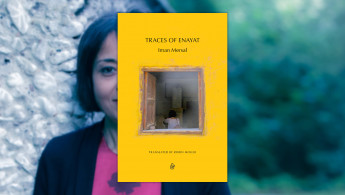

Traces of Enayat: Uncovering the life of Egyptian female writer Enayat al-Zayyat

In Traces of Enayat (And Other Stories, 2023), the author embarks on a compelling journey to uncover the life of an Egyptian female writer.

Iman Mersal blends biography and autobiography, offering insights into the research process and introspection.

The narrative revolves around Enayat al-Zayyat, whose only book Love and Silence was published posthumously following her tragic suicide in her early twenties, upon hearing of various rejections of her manuscript.

Mersal’s exploration of Enayat’s life, drawn from fragmented narrations and articles, reveals the challenge of uncovering concealed truths.

The absence of material related to Enayat highlights the loss of cultural memory. Remembered as a wife, mother, and later a single mother challenging societal norms, Enayat’s story remains largely hidden.

Mersal reflects on the significance of personal archives, stating, “It is not a documentary record of oneself but rather a narrative. Not, then, a disconnected assemblage of facts, or truths about that person, but a life’s worth of needs and desires, dreams and illusions: a record of their mutual misunderstanding with the world.”

"Oblivion emerges as a recurring theme in Mersal's journey, as she uncovers scattered remnants of Enayat's life and the hidden truths behind them"

The personal archive, Mersal soon discovered, did not exist. All that remained was “just thirteen pages, eleven handwritten and two typed, a grand total of 1,820 words divided between the apartments of Nadia Lutfi and Azima al-Zayyat”; her friend and sister, respectively.

Oblivion emerges as a recurring theme in Mersal’s journey, as she uncovers scattered remnants of Enayat’s life and the hidden truths behind them.

All of Enayat’s journals were destroyed in the same year following her suicide – the same went for her letters and unpublished literature. What remained of Enayat was conventionally respectable to stave off the possibility of further questions.

However, Mersal’s own investigations and meetings with people who knew Enayat elicited information that contrasted with previous narratives, or shed light on the known facts. Speaking to some of Enayat’s relatives, for example, shed light on the untimely death of Enayat’s son at a young age – a possible suicide.

The narrative also delves into Egypt’s political, social, and cultural landscape, intertwining with Enayat’s story and Mersal’s reflections.

At times, the backstories of places intertwine with the author’s recollections and personal anecdotes. But the story swiftly turns to Enayat and Mersal’s own musings, of her expectations, and her dreams juxtaposed against the absence of a writer which was more than present in Mersal’s consciousness.

A few diary entries by Enayat reveal her struggles as a married woman abused by her husband: “You are a woman adrift: all at sea and a brute for a husband, with his noontime demands, his long snoring sleeps, and not one tender word or caress.”

With each discovery, Mersal visits places and people associated with Enayat, including the mental health institute where she spent much of her life.

For Mersal, finding Enayat’s tomb symbolises a connection with the writer. “For her life, I had to return to the archive, to the memories of the living and my own imagination, but I felt now that at last, she trusted me, that she had allowed me to reach her along a chain of chance and speculation,” Mersal writes.

But it is towards the end of the book that Enayat’s emotional essence is unveiled, bringing Mersal’s investigations back to a line that haunts the reader since its utterance: “A happy woman cannot kill herself over a book.”

Even as Mersal ponders the contradiction of the statement, she realises her own flaw in overlooking human emotion and the tragedy that may be associated with it. The revelation that Enayat was writing a second book, the tragedy of a love that could not be fulfilled, and the ensuing suicide.

"Oblivion and absence in the archives, among female writers, the destruction of her personal archive - Enayat might have been completely silenced, or normalised as silent"

What stands out in Mersal’s book is the absence of Enayat despite her relevance – a fact which Enayat herself commented about in a journal entry in 1962: “I don’t mean a thing to anybody. Lost, found, it’s all the same: Here is as good as gone. The world wouldn’t tremble either way. When I walk I leave to tracks, like I walk on water, and I am unseen, invisible.”

Oblivion and absence in the archives, among Arab female writers, the destruction of her personal archive – Enayat might have been completely silenced, or normalised as silent.

As Mersal describes her quest, “The destruction of Enayat’s archive felt like a catastrophe, but its absence sent me after the traces of its erasure.”

Ramona Wadi is an independent researcher, freelance journalist, book reviewer and blogger specialising in the struggle for memory in Chile and Palestine, colonial violence and the manipulation of international law

Follow her on Twitter: @walzerscent